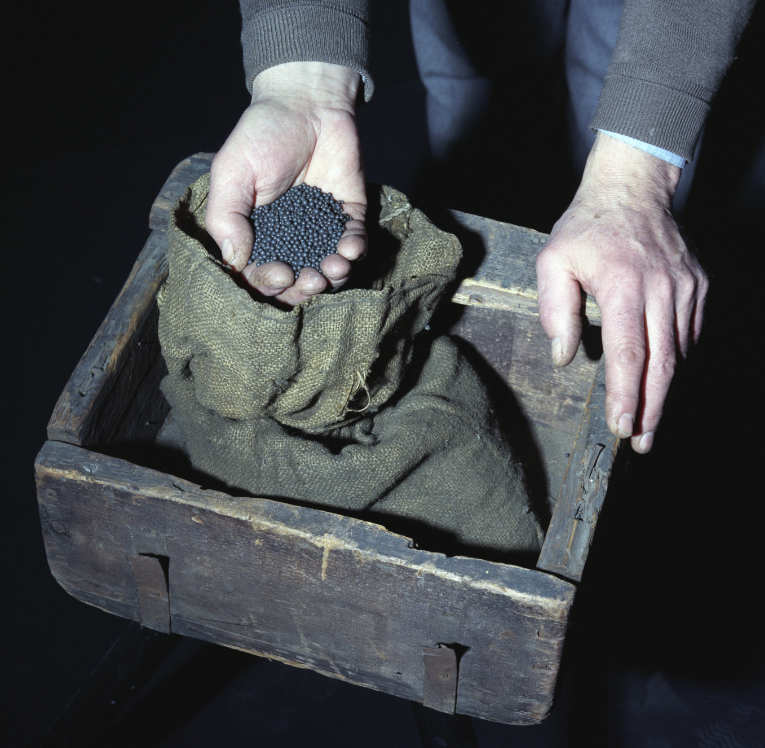

On May 15, 1855, the crime of the century was perpetrated by turning lead into gold. Enacting a highly sophisticated bait and switch, Edward Agar, William Pierce, Jeremy Forsyth, and James Burgess were able to steal £12,000 in gold which was being transported from London to Paris. This highly publicized crime, the Great Gold Robbery, and ensuing trial became great Victorian fodder for tabloids and social gossip. About one hundred years later, Michael Robbins wrote a feature piece in the May, 1955 issue of The Railway Magazine. Twenty years later, Michael Crichton took this sensational story and turned it into a stunning piece of historical fiction. The Great Train Robbery is highly fictionalized but close enough to the truth to be spellbinding.

I was introduced to Michael Crichton’s books in middle school. Long before Jurassic Park hit the big screens, I first forayed into Crichton’s writing with The Terminal Man and The Andromeda Strain. These two books, read in rapid succession, whetted my appetite for medical-based science fiction. They presented intellectual puzzles for me to solve with the assistance of the narrator, and made me genuinely interested in technology, medicine, and cerebral fiction. As intriguing as Crichton’s writing was, it was often unsatisfying because of his one-dimensional characters and what almost seemed to be a compulsive need to throw in something sexual and scandalous. Compared to C. S. Lewis’s Space Trilogy, which I would not discover for almost two more decades, or Carl Sagan’s Contact, Crichton pales in comparison. That said, his work is not without value.

What Crichton seems to excel at is his ability to recognize and understand complex technical challenges that can be massaged into interesting stories. The question which propels Andromeda Strain forward is riveting. The moral challenges in The Terminal Man are frightening in their possibilities. It is this ability to know a good story when he sees one and harness the technical complexities as rising action that make The Great Train Robbery a truly exciting story to read. The real life facts are awesome indeed. Presuming that his readers might have some familiarity with the true story, he shifts the role of criminal mastermind from the real main character to a lesser character and re-dresses them both with more intrigue. Frankly, it is a very smart move. Instead of having to develop a plot, all he has to do is retell the story in a way that people will want to read. And, he did.

In Crichton’s version of events, William Pierce is the gentleman genius. Presumably not well-versed in Victorian literature, Crichton seems to have patterned William Pierce after Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes. Edward Agar fits nicely into the role of Dr. John Watson. While readers will spot the similarities, and Pierce and Agar are criminals, not crime solvers, it doesn’t feel uncreative. In fact, it is almost a joy to think of these real life men as being something like Holmes and Watson. Since the setting is obviously Victorian London, it is a highly technical crime, and Crichton seems to have done excellent research, it was fun to read.

Typical Crichton, however, there are some passages which are tawdry and offensive. Frankly, it is a darn shame. These scenes add nothing meaningful to the story, and they throw mud on an otherwise fascinating and entertaining heist. One chapter in particular is sexually disgusting and totally unnecessary, another is painful to read in its descriptions of dog fighting, and another is a gross recounting of Native Americans and the “savage” buffalo hunting practices.

While this is one of my favorite Michael Crichton novels, and I will keep the audiobook, I will refrain from purchasing the printed book for my shelf. The objectionable scenes make me want to be cautious about having this around young readers. Crichton’s inclusion of these scenes sufficiently denigrates the book from being a necessary addition to my limited shelf space.

I listened to this one via Audible and enjoyed Michael Kitchen’s (Foyle’s War) narrating immensely.

Conservative readers will want to know that there is some foul language in this story.

Because the Chapter titled “Assignation,” is quite vile, I would like to give readers several ways of dealing with it that don’t involve waiting for it to appear in your text:

PREVIEW THE SCENE: If, however, you would like to preview it, it is quoted below.

SKIP THE SCENE: If you do not wish to read it but would like to know how it advances the plot, I will summarize the chapter below with a clear notation. If you wish to skip the chapter when reading in your book, be on the lookout for Chapter 19. If you are reading on Kindle, it is Kindle pages 130-132. If you are reading via Audible, it is “Chapter 20.”

This concludes the review. Below this point are the spoilers pertaining to the sex scene.

SPOILERS – SPOILERS – SPOILERS

Summary: Mr. Henry Fowler is a keyholder who keeps his safe key around his neck at all times. Fowler has a painful venereal disease which he believes can be cured or relieved by having sex with a virgin. (This is explained one or two chapters before this scene.) The “fresh” girl that Pierce hires to “help” Mr. Fowler is a 12-year-old orphan from the country who begs Fowler to remove the key from his neck during their interlude so that it won’t scratch her. Obliging her, the key is left unattended, the criminals take a wax impression of it, and return the key without Fowler being any the wiser.

Preview:

Mr. Henry Fowler could scarcely believe his eyes. There, in the faint glow of the street gas lamp, was a delicate creature, rosy-cheeked and wonderfully young. She could not be much past the age of consent of twelve, and her very posture, bearing, and timid manner bespoke her tender and uninitiated state.

He approached her; she replied softly, halting, with downcast eyes, and led him to a brothel lodging house not far distant. Mr. Fowler eyed the establishment with some trepidation, for the exterior was not particularly prepossessing. Thus it was a pleasant surprise when the child’s gentle knock at the door received an answer from an exceedingly beautiful woman, whom the child called “Miss Miriam.” Standing in the hallway, Fowler saw that this accommodation house was not one of those crude establishments where beds were rented for five shillings an hour and the proprietor came round and rapped on the door with a stick when the time was due; on the contrary, here the furnishings were plush velvet, with rich drapings, fine Persian carpets, and appointments of taste and quality. Miss Miriam comported herself with extraordinary dignity as she requested one hundred guineas, her manner was so wellborn that Fowler paid without a quibble, and he proceeded directly to an upstairs room with the little girl, whose name was Sarah.

Sarah explained that she had lately come from Derbyshire, that her parents were dead, that she had an older brother off in the Crimea, and a younger brother in the poorhouse. She talked of all these events almost gaily as they ascended the stairs. Fowler thought he detected a certain overexcited quality to her speech; no doubt the poor child was nervous at her first experience, and he reminded himself to be gentle.

The room they entered was as superbly furnished as the downstairs sitting room; it was red and elegant, and the air was softly perfumed with the scent of jasmine. He looked about briefly, for a man could never be too careful. Then he bolted the door and turned to face the girl.

“Well, now,” he said.

“Sir?” she said.

“Well, now,” he said. “Shall, we, ah …” “Oh, yes, of course, sir,” she said, and the simple child began to undress him. He found it extraordinary, to stand in the midst of this elegant—very nearly decadent—room and have a little child who stood barely to his waist reach up with her little fingers and pluck at his buttons, undressing him. Altogether, it was so remarkable he submitted passively, and soon was naked, although she was still attired.

“What is this?” she asked, touching a key around his neck on a silver chain. “Just a—ah—key,” he replied.

“You’d best take it off,” she said, “it may harm me.” He took it off.

She dimmed the gaslights, and then disrobed. The next hour or two was magical to Henry Fowler, an experience so incredible, so astounding he quite forgot his painful condition. And he certainly did not notice that a stealthy hand slipped around one of the heavy red velvet curtains and plucked away the key from atop his clothing; nor did he notice when, a short time later, the key was returned.

“Oh, sir,” she cried, at the vital moment. “Oh, sir!” And Henry Fowler was, for a brief instant, more filled with life and excitement than he could ever remember in all his forty-seven years.

Crichton, Michael. The Great Train Robbery (pp. 130-132). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.