The Inquisitor’s Tale by Adam Gidwitz is a blend of ridiculousness, beauty, intrigue, and deep questions. I wanted to love it for its creativity. But, after reading it for a while, I wanted to dismiss it for its crassness. I wrestled with this text throughout the entire reading process. When I turned the last page, I discovered thirteen pages of endnotes. Because the final chapters were lovely and inspired, I committed to reading the endpapers. It was there that I realized I had read this book all wrong. I hope that in this review I can help my readers understand the book just enough to try to get the marrow out of the bones of this text. Because, ultimately, there is something good at work in here. Something that is probably worth the effort.

One friend mentioned to me that the book became truly alive for her on page 280, and made all of the investment worth it. I found that both reassuring and frustrating. Reassuring because, perhaps there was something coming that would make enduring the farting dragon worthwhile. But also frustrating because, why would an author make us wait 280 pages to fall in love with the story? Taking her word for it, I kept reading. And even though page 280 wasn’t particularly meaningful to me, I did see how the story was growing in substance and value.

I never do much research in anticipation of a book I am going to read. At my Tuesday Night Book Club recently, another Great Books College graduate and I were talking about how our colleges taught us to enter into a story with as little preparation as possible so as to have the most authentic reading experience possible. Comprehension and context could happen on a second read. The first read, the virgin read, was supposed to be uninformed by anything other than our personal reading experience. And yet, at this club meeting, we were lamenting this training when it came to reading authors like Dante. We realized that when we are so far removed from the culture of a story, we might not be able to enter into it at all without some preparation. I think this might be the case for The Inquisitor’s Tale because this book isn’t working on a modern scheme. It attempts to be something authentically inspired by the thirteenth century and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

“I hope, if nothing else, this book has convinced you that the Middle Ages were not ‘dark’ (never call them the Dark Ages!), but rather an amazing, vibrant, dynamic period… the High Middle Ages was a time of cultural collaboration and collision. It was, in that way, very much like today.”

– Adam Gidwitz, Endpapers

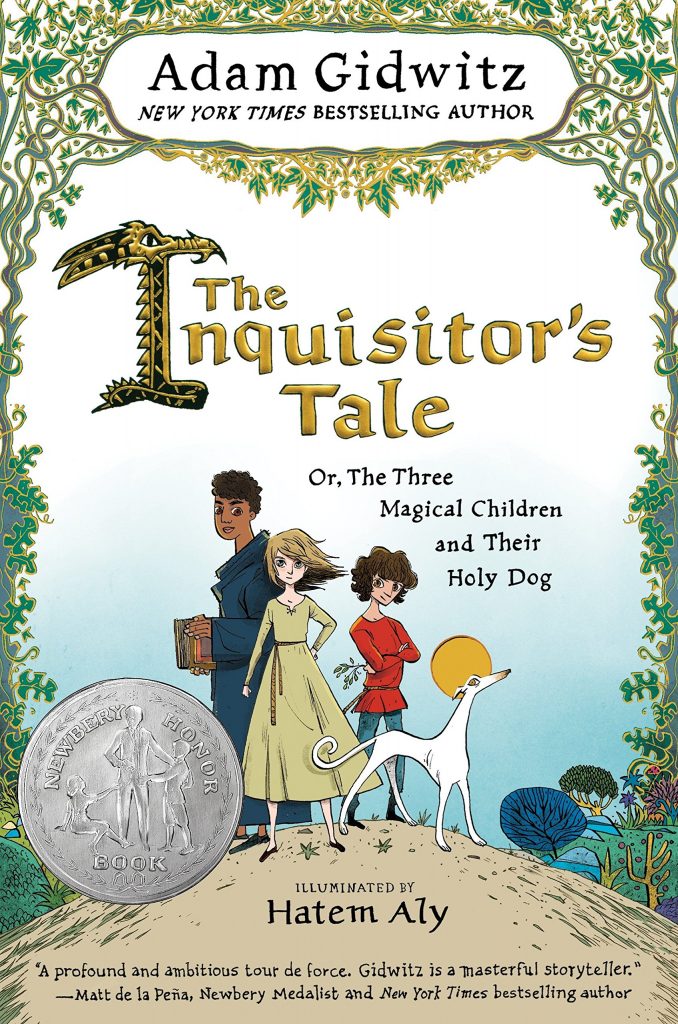

Using a format like that of the Canterbury Tales, this novel follows the beautiful friendship and exploits of three children and the miraculous dog who accompanies them. Like the Canterbury Tales, each chapter is told in the voice of a different storyteller – “The Nun’s Tale,” “The Brewster’s Tale,” “The Jongleur’s Tale,” etc. Also like the Canterbury Tales, those voices are heavily accented, and tell the story through the prejudices of the particular storyteller. I struggled with this because I thought the concept was brilliant, but the execution was lacking. I loved how Gidwitz made each storyteller his own character with a unique voice, but I was saddened by the insertion of unnecessarily modern language commonly found in children’s literature today. I felt like he was dumbing down his writing to make it appealing to a younger audience than the text really should be addressed to.

Jeanne, a peasant girl from a small village, is patterned off of the real Joan of Arc. William, inspired by the real Guillaume d’Orange, is the son of a Spanish lord and his African Muslim mistress. He is being raised by a Benedictine monastery where he is an oblate. Jacob, not inspired by anyone in particular, but rather by the plight of the Jews generally in Europe at that time, is the child of French Jews, and the nephew of a famous Jewish scholar. The “holy dog,” Gwenforte, is based on the famous dog Guinefort (or in Wales, Gelert) who saved the life of a child from a serpent, and was revered by the local villagers.

Each of the children has a divine gift that makes them outcasts but also heroes. Jeanne, like Joan of Arc, is a child touched by Divine Grace, and has visions of the future. Massive in size and as strong as Paul Bunyan, William has superhuman strength, but also incredible intelligence. Like famous Jews of that time, Jacob has the gift of healing. He uses herbs and prayers to miraculously heal people (and dragons). Recruited by a Viking-like monk, the children are on a mission to save something absolutely worth saving. Along the way, they encounter prejudice, must overcome spiritual obstacles, and extinguish their own self-doubt.

The story itself is compelling and relatively fast-moving. The unique voices of the storytellers add texture to the story by giving us a multi-faceted view of the story and the children. This tale celebrates friendship, goodness, and spiritual conviction, and it does that well.

After some hours of walking, Jacob says, “I read something interesting in the Talmud last night. After you had all fallen asleep.”

“Wasn’t it too dark to read?” Jeanne asks.

“I sat by the door, and the moon was full.”

“What did you read?” says William.

“I read a line that said, ‘You are like pomegranates split open. Even the emptiest among you are as full of good as a pomegranate is of seed.’”

I choke on the thickness that rises in my throat. After my humiliation last night, and the forgiveness I received, I can only hope that is true.

Here is where the endpapers would have been a blessing to me had I read them before reading the text. Without context, this story feels very much like Monty Python. A farting dragon, “foul fiends” who are zombie-like brigands, knights crawling stupidly through a dung heap, dogs who come back from the dead, and a drunk monk. That kind of story does not appeal to me, and I nearly gave up, frustrated, in several places. But then, pockets of beautiful writing would break-in and my interest would be renewed. Had I known that the farting dragon was not a crude invention designed to make ten-year-old boys laugh themselves silly, but rather a true story, I may have been less offended by its inclusion. Gidwitz explains that the idea came from a book of saints’ lives from 1206 called The Golden Legend by Jacob de Voragine.

Overall, the story is fun and educational. Gidwitz’s research is incredible, and the reader is treated to something that is part fairy tale, part legend, and part living history. Also, underneath the (sometimes crass) humor, there is real heart to this tale. Gidwitz is showcasing the real prejudice Europeans had against the Jews and the Africans. Also, he presents both good and bad Christian characters, highlighting the inconsistencies of the age and the hardships endured by regular people at the hands of corrupt rulers and church leaders. As a devout Catholic who has studied this time period, I did find his characterization of the Church to be a bit unfair. I freely admit that corruption in all circles was rampant, but I think that most of the Christian adult characters in this story were more or less evil, and that is not representative of the time. I think Gidwitz could have been more balanced in his character development.

Mercifully, unlike Canterbury Tales, there is little to nothing of sexual humor in this story. There are one or two comments about William’s father being a philanderer, but that is about it.

Christian readers will want to know that there is some religious confusion in this story. In an important scene, we meet a Jewish scholar and a fiesty Catholic monk. They are best friends, and they tease each other deeply about the errors of the other’s theological beliefs, but their love for each other is evident and beautiful. The children have a similar situation between themselves. It is really lovely.

However, Gidwitz is clearly advocating for a Universalist point of view – that all religions are true and that man can find salvation in any of them.

“So, yes, I believe you are a saint.”

Yehuda said, “Even Jacob? A Jew?”

“Of course there are Jewish saints… and Muslim saints, and saints in lands where they worship God in all sorts of ways.”

Further, his use of the words “saint” and “martyr,” and his eventual explanation of those terms, is inconsistent with Catholic teaching; therefore inconsistent with thirteenth-century understanding. His use of angels and demons is also more fairy tale than thirteenth-century Christian. Also, he makes some technical mistakes which might be jarring to Christians, and specifically, Catholics. For example, he describes monks in one scene whom he labels as Dominicans, but then he clothes them in brown woolen tunics, when Domincians wear white albs and black capes.

Ultimately, there is some especially bad moral relativism pertaining to the kids hearing the voice of God and obeying that voice. He has the characters succumb to overriding their consciences and their moral formation because their hearts are telling them to break certain rules. The strange part is that not all three of the children really agree, and I was left with the impression that the author himself is seeking, and perhaps wrestling with his own conscience.

I think The Inquisitor’s Tale could be a wonderful resource for readers who are preparing to study The Canterbury Tales or the Middle Ages. I think Christians should be aware of the religious challenges in this text, and that they might want to use those problems as opportunities for discussion and better formation.

I think the target age range (9-11-year-olds) is off. I would not hand this book to my under-twelve-year-olds. But I would have no problem giving it to my middle and high school children.

I read the text with the interesting marginalia, and have not listened to the Audible, and therefore cannot comment on that production.

It is worth noting that the author has composed an educational guide to go with the story.