Oh, how I would have loved Margot Benary-Isbert’s The Ark when I was a teen! The Ark’s main character, Margaret Lechow, is a lovely soul whose sympathy with animals resonates with my own deep longing to have been raised on a farm. Like Margaret, I was never more comfortable anywhere than when I was at friends’ farms full of calves, ducks, dogs, and chickens. Also like Margaret, I have a fascination with herbs and the earth, and I too hope to keep chickens and bees in the near future. While I was reading this captivating story, I felt that I understood Margaret, and I am sure that I would have cherished her had I read her story during my awkward and lonely pre-teen and teen years.

Not only would I have loved this story then, but I also love it now. On Thursday, I sat down to read a chapter while I had a mid-afternoon cuppa tea and it turned into two cups of tea and 32 pages. Then, that night, I stayed up way too late reading another 100 pages. And when I awoke in the morning, I returned to it as soon as my prayers and obligations were met. I just could not put this book down. It was so full of beauty and lovely storytelling that I just had to drink it all in a few large gulps.

“At home, in Father’s bookcase, there had been a book about the wanderings of Odysseus. Ulysses, too, had wandered about the world for many years after a war before he finally found his way back home.”

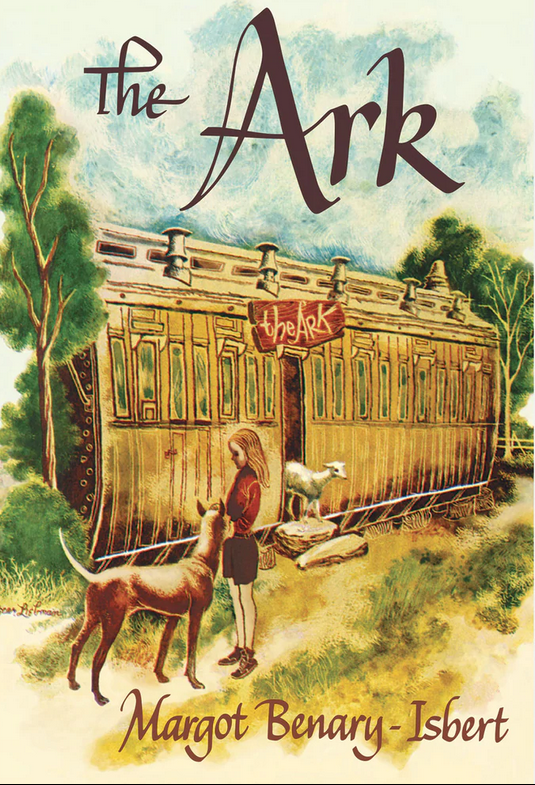

Jill Morgan of Purple House Press recommended The Ark by Margot Benary-Isbert to me because she knows how much I love Hilda van Stockum. She thought this might be a little like one of van Stockum’s lovable stories. She was right. The Ark was published in 1953, but is set in post-war Germany after the Second World War. Like van Stockum’s books, this one centers on the life of a family. The Lechow family has suffered terribly during the last three years of the war. Father was captured and is a Prisoner of War in a Russian camp. In their native Pomerania, Mother and the children witnessed the death of Margaret’s twin brother, Christian, and their dog Cosi, before they were taken from their home and sent to live in one refugee camp after another. Finally, the Housing Office has given them a permit to live in West Germany, far from home. As they have moved from camp to camp and now to Hesse, they leave notes at camps and train stations as breadcrumbs for Father to find and use to follow back to them.

When the Lechows got to Hesse, they were assigned to live in the cold attic in the house of an elderly widow who thought that she did not like children. Times were hard for everyone, but the Lechow family had really been blessed in their housing assignment – two neat, clean, dry, attic rooms all to themselves. So many of the other refugees were living in cellars, barns, and other nearly uninhabitable hovels. Gratitude seasoned everything the Lechows said and did, even when Matthias had to work construction, Margaret had to stand in lines for hours for everything, Andrea had to constantly talk their landlady into loaning more necessities, and Joey had to suffer the indignity of school. The Lechows were grateful for their blessings and freely shared with others in need. Ultimately, they did make friends with many including the old landlady, Mrs. Verduz. But, grateful as they were, nearly everyone felt that they were holding their breath waiting for real life to return.

“Now I know why you have to knead and pat the udder when you milk; the young do the same. Listen to the way they smack their lips. Oh, Mrs. Almut, isn’t it marvelous?”

“It is!” Mrs. Almut said. “People who don’t feel the marvel ought to let animals alone. Nothing does well if you don’t put your heart into it. Even the soil feels whether you like it or not.”

While reading, I felt like this story would be what would have happened if Hilda van Stockum, Maria von Trapp, and James Herriot had collaborated to tell a story about family and farm life in rural post-war Germany. The Lechow family is Catholic, and we are treated to scenes with Advent wreaths and other liturgical observances that feel like they come right out of Around the Year with the von Trapp Family. The family itself is truly the main character of the story just like in van Stockum’s books, especially Five for Victory. And, when Matthias and Margaret’s luck finally changes and they are taken in by a vivacious and resolute farm widow as hired hands, we have pages and pages of delightful old-fashioned farm stories that remind me of James Herriot. I love all three of those authors and considered this to be a particularly wonderful treat. I was especially captivated by the breeding of the dogs and the way in which Margaret’s love of animals and farm work animated her whole self. She and Mrs. Almut are a matched set, and their friendship, forged in the caretaking of noble beasts, is one of the best parts of this book, and seasons the sequel with the best flavors.

“That’s the way it is when what you have loved best departs. There’s a long time afterwards when you’re never at home anywhere. But wait, the dead come back. They come to life again within us; we only have to have patience and let it happen.”

Animal-loving readers will be pleased and relieved to know that the animal stories in this book are nearly all success stories. A couple of puppies do die after an illness and some animals are taken away to be slaughtered, but none of those are main scenes and are minimal in comparison to the many animals who thrive and have babies and make the farm more lovely. Margaret is haunted by the loss of her twin brother and her Great Dane Cosi (which occurs before the story begins), but the Almut farm heals much of those wounds and brings her heart back to life again.

“Our rations aren’t even enough for ourselves,” Margaret said.

“Never mind, you bring him along now and then,” Mother said. “Where there are meals for five there’ll always be a grain of corn for a sixth member of the flock.”

Readers who have adoption in their lives may appreciate the story of Hans Ulrich, the son of a war-lost father and bombing victim mother who died before she could properly identify herself or her son. Kindergartener Joey Lechow meets Hans at school and the two become inseparable. The good soul that Mrs. Lechow is, she always makes room for Hans in her heart and home. Mrs. Verduz, who doesn’t like children, also finds herself entertained by Hans and pleased to have him so constantly traipsing up and down her stairs. Ultimately, an adoption process for Hans begins, but in the sequel to this book, it changes. By the time the second book ends, Hans is a very loved little boy with a permanent place in the Lechow family, no matter how non-traditional it may be.

The war was horrible for everyone. While most of the WWII books I have read have been from the point of view of the occupied, this one, like Hilda van Stockum’s Borrowed House, is told from the German perspective. This one is set after the war, of course, but the devastating effects of the war are universal. The stories of hunger, loss of limbs, and lost family members cut us to the heart. They are all presented in a way that is good and appropriate for young readers, but they are not easily ignored.

Some families may wish to know about one particularly tragic storyline as it might raise questions. Like everything in this story, this is handled with much grace. Nonetheless, Mrs. Almut’s neighbor is considered to be the village witch. Of course, she is not. In fact, Marri reminds me of Gene Stratton-Porter’s “Bird Woman” character in Freckles and Girl of the Limberlost. Marri’s husband is dead, and her only son was executed by the Germans because his beliefs in nonviolence towards all living creatures prevented him from joining the army as a soldier. Marri is a beekeeper and has a vibrant herb garden. She has a robust understanding of how herbs can be used to help and heal. She is a good soul who is nursing a terrible heartache, but she is generous and lively and becomes one of the Lechow family’s dear friends.

“How can I explain it to you, child? I know what people say. Some say he was crazy, others that he was a coward. None of it’s true. I knew Ludwig from the time he was a baby. He was just one of those people who wanted to take Christianity seriously, you understand? Love your enemies and thou shalt not kill – he took it all literally. They didn’t give him much of a chance during the war. Either-or, they said. Kill or be killed . . . the finest porcelain is the soonest broken. And yet those are the people we need most now, in these difficult times when a new world has to be built. But Marri has got it into her head that his death was her fault. ‘I should have raised him differently,’ she says. ‘In a world of wolves, you have to learn to howl with the wolves . . .’ It takes time to heal sorrow.”

I think the target audience for this book and its sequel Rowan Farm is about 12 and up. My eleven-year-old will love this one, but may not be entirely ready for the sequel. My thirteen-year-old will love both, but I will want to chat with her while she reads the sequel. The content and the writing are about two steps up from Hilda van Stockum’s Winged Watchman or Five For Victory, and one step up from her The Borrowed House. Also, the storyline focuses a good bit on the middle teenagers in the family. In the sequel, the introduction of dating and potential marriage takes center stage – all chaste and wholesome, but not interesting to younger readers.

One small content comment: Matthias and Joey have a pretty normal brotherly relationship. Some parents might wish to know that Matthias does do a bit of name-calling of Joey. And Joey does a bit of barking back. None of it is scandalous, but words like “twerp” are used on a few occasions. If parents are wishing to avoid name-calling, this book might warrant a pre-read.

I continue to be amazed by how many gems I have never heard of and am now discovering because of the revival of older children’s literature that is happening right now. So many of us owe a debt of gratitude to publishers like Purple House Press for bringing timeless and wonderful stories like this back into print. I read the Purple House Press edition of this book which included the addition of a few pages on the life of the author and some additional context which enriched my reading. Readers may wish to read that note at the back of the book before beginning the story itself.

Yesterday I stopped into what used to be a fantastic used book store in Milwaukee. The owner continues to offer gems, but over the years I have noticed that the vintage novels and vintage children’s books sections were in serious decline. Yesterday I did not find a single vintage children’s book worth buying that I did not already own. And the only vintage novel I found was a three-volume Kristin Lavransdatter priced at $45 per volume (too rich for my budget). I asked the shopkeeper why the sections were in decline. We had a sad chat about the scarcity of good books. Those of us who can spot them and still value them have been assiduously collecting them. Those who can’t are disposing of the ones they inherit, thus preventing the rest of us from having a chance at them. Worthy old books have always been a finite resource, and it appears that that well is starting to dry up. The shopkeeper did say that he is particularly impressed with small publishers like Purple House Press for the work that they are doing to preserve these classics so they are being printed well and being “saved” for all of us. I agree.

You can learn more about Margot Benary-Isbert and this book at Biblioguides, here. You can purchase this book from Purple House Press, here. You can purchase this book from Amazon, here. You can read our review of the sequel, Rowan Farm, here.