I am frustrated. And disappointed. Some may call me a pearl clutcher for this review, but I think it is important that I share my thoughts on this historical fiction novel as honestly and directly as possible so that mothers and librarians can decide whether or not to consider this story for their particular readers.

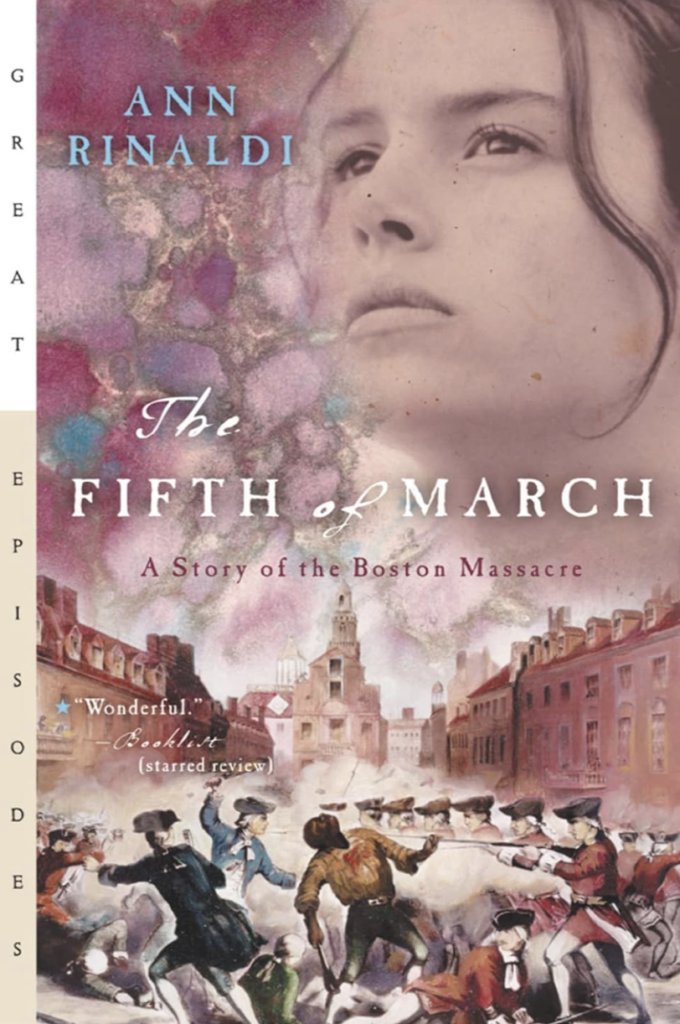

The Fifth of March by Ann Rinaldi is a compelling historical fiction novel about the Boston Massacre of 1770. Young orphan Rachel Marsh is an indentured servant in the household of John and Abigail Adams. When the story begins, in 1768, Rachel is a sweet, thoughtful, and trustworthy nursemaid to the Adams children. As the events of 1770 unfold, however, Rachel goes through a transformation that the author seems to approve of, but I was disappointed in.

This review will, by necessity, be full of detail from the story. First, however, I will give some general thoughts that can be read without spoiling the outcome of the story.

As history has made clear, life in Boston in 1770 was complicated. “Plain Americans” instead of “British Americans” were just beginning to awaken to the notion that they could be something other than subjects to the Crown. Not all Americans were roused to the idea at the same time nor with the same fervor.

In The Fifth of March, Rachel Marsh has escaped an abusive relationship with her greedy uncle and has been taken under the wing of the genteel, kind, and thoughtful Abigail Adams. When a British ship with the 29th Regiment arrives, however, things change for Rachel. Her natural human sympathy for the underfed British sentries leads her into a relationship with Matthew Kilroy. That relationship is complicated and fraught with trouble. Rachel finds herself torn between wishing to be a plain American, like Sam Adams, while also remaining loyal to her good employers who are not yet ready for revolution, and her growing concern for the British Kilroy. We see the Boston Massacre through her eyes and witness the aftermath as it touches nearly every corner of Rachel’s life. The story ends with the Adamses removal from Boston back to Braintree at the conclusion of the massacre trials.

The concept for this story is brilliant. Through the young maidservant, we have a front-row seat to one of the most tumultuous times in our American story. I have loved John and Abigail Adams since reading David McCullough’s John Adams over ten years ago. When I finished that biography, I felt as if I had moved in with the Adams family for a few months, and I found myself missing them when I was done reading. This story gave me the joy of moving back in with them for a few hours.

From here on, I will get into the details. If you wish to avoid spoilers, this is a good place to stop.

Ann Rinaldi knows how to spin a good yarn. She develops interesting characters and places them in exciting places. In this novel, her young female protagonist is drawn well and reads like a girl of her age should. Rinaldi captures the confusion and tension that commonly exist in the lives of young women who are coming of age. I was delighted to see that she put Rachel into the care of such a thoughtful and wise mistress and mentor as Abigail Adams. I wish she had developed Abigail a bit more, as I think that would have made the story more interesting. Having not done so, however, made it easier for Rachel to rebel. Maybe that was the point?

When Rachel brings food out to Matthew Kilroy, it seems to be the decent thing to do. The British sentries are cold and underfed. Her human compassion is laudable. The Adamses turn a blind eye to the entire endeavor. Honestly, I found that unbelievable. And too convenient.

With each meal Rachel brings out, she and Matthew have more conversation. Matthew is a sympathetic character, and this takes on a bit of a Romeo and Juliet theme. However, Matthew is often moody and aggressive with Rachel. He is always pressing her to walk out with him, hold his hand, and kiss him. When she objects that the Adamses might not care for her to be walking out with a redcoat, he manipulates her emotions and cajoles her. I was very discouraged by this theme and the persistence of it throughout the story.

As the story progresses, some of Rachel’s friends warn her that Kilroy is a troublemaker and a cad, but Rachel chooses not to believe it. In fact, her uncle tells her that her own mother was pregnant with Rachel out of wedlock and warns that if she continues on this path with Matthew the same will befall her. When, after the riot, John Adams specifically forbids her from visiting Matthew in prison, she disobeys him and goes anyway every week. Throughout, Matthew is always pressing Rachel for more affection and attention than she is willing to give. Rachel feels deeply conflicted by it all. I think Rachel’s turmoil over her feelings about a man who is always dissatisfied with her is a bad example for our teen readers, especially since it doesn’t resolve particularly well.

When John and Abigail discover Rachel’s disobedience, they assume some of the blame for themselves. I was disgusted by this. Firstly, I do not think it is consistent with the character of the real John and Abigail Adams. And secondly, because I think that it is bad parenting, bad leadership, and a bad example for our young people to be reading. John does more or less terminate their agreement with Rachel, but he provides for her richly and does nothing to admonish her for violating their trust in her and dragging their names into slanderous gossip. It struck me as a bad situation made worse by a bad resolution.

Whenever Rachel goes to the prison to bring Matthew food and visit with him, she is searched by a Quaker woman who works alongside the guard. The Quaker is extremely kind to Rachel, but she offers Rachel terrible counsel, telling her that these forbidden visits were actually “an act of charity,” and that a nursemaid who is so charitable should be thought of by her employers as a most valuable influence on their young children. What nonsense!

Finally, at the end of the book, Rachel leaves the service of the Adams household. They provide her with a dowry chest, many valuable and beautiful goods, a bag of silver, and a position in a commodious situation in Philadelphia. Mr. Adams even pays for her passage and an escort to Philadelphia. Rachel, who loves the Adams family, decides to leave in the very early morning with only the clothing on her back and the small piece of luggage that she brought with her when she joined their service. She leaves a letter that she says will help the family understand why. But, we as readers, never really understand why. Instead of going to Philadelphia, she joins up with the revolutionaries. It was a strange ending that left me discouraged.

I can only speculate that Rinaldi thought she was inviting young readers into challenging questions that are timeless and common for their age group. And, to a certain extent, that is true. However, I didn’t appreciate how those questions were answered and would prefer to find some better alternatives to give to my readers.

Overall, the story is not scandalous, but neither is it entirely wholesome.