“Gradually these people, conquerors and conquered, mingled and became one race and the mixture is richer for what each has brought. In spite of wars and cruel oppressions there has always remained an unquenchable love of liberty and justice in the heart of this race. Because of this, in the courage of centuries, slowly with long delays and many reverses yet persistent and enduring, this people has framed a way of government which has made and kept them the freest people on earth.”

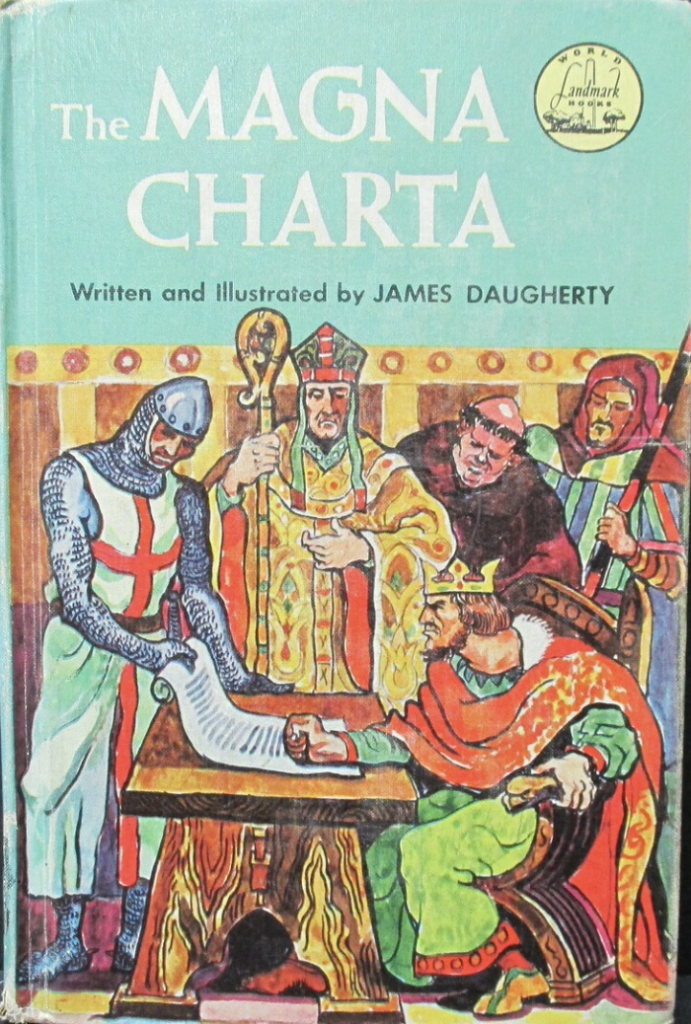

Written with powerful and romantic prose, James Daugherty invites us into the exciting drama of the Magna Charta. He opens with a prologue titled “The Magic Island” that reads like the introduction to epic poetry and then gives us a most handy family tree to help us follow along through the twists and turns of wars, power struggles, and political intrigue. Then, he breaks the story into four parts: “The Twelfth Century,” “The Angevins,” “King John,” and “The Magna Charta.” Then a most fascinating final forty pages titled “The Children of the Magna Charta.” This last section is not only deeply interesting but it is also essential to understanding the Magna Charta itself and the ramifications of that revolutionary act.

“If you were living in the twelfth century in England you would be somebody’s vassal. Nearly everybody in the twelfth century was someone’s vassal. The king and the bishops were the Pope’s vassals. The barons and even many bishops were the king’s vassals. The knights were the baron’s vassals. The farmers were the knights’ tenants and the laborers or villeins, as they were called, were the vassals of practically everybody . . . This system of vassalage was called ‘feudal.’ It was a great improvement on the violence and disorder of previous ages. It was a snug and complete society in which everyone had his place in a sort of pyramid in which each was dependent on and subject to another . . . If you were a young man living in the latter half of the twelfth century, you would often be following your lord to war with or against King John in England and France. And you would be taking part in and talking about many of the events that happened in the following true story.”

In the first section of this book, Daughtery sets the stage. Over the course of four pages, he explains the feudal system and how everything was interconnected and co-dependent. But he does it in such a way that the young reader can picture the setting and their place in it.

In the next two sections of the book, Daughtery switches back to his more romantic tone and tells us the story of the people, their relationships and their reasons for fighting. He draws us into the kind of story that feels like our favorite legends of Robin Hood, King Arthur, and Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe. He makes it magical and true at the same time, and it is exciting to read.

In the fourth section of this book, Daughtery shows us what the Magna Charta really means, to whom it matters, and why. And the answer is: it matters to us. The Magna Charta was the first formal statement of self-government in recorded history. And from it, many children have descended. Daugherty gives us a few pages on each of the major heirs of this lineage of freedom from the Mayflower Compact to the United Nations Peace Treaties. He helps us to understand why the American experiment was possible and why it succeeded. Daughtery does a magnificent job helping us to understand our place in this great drama started in the twelfth century. This book is in the “World Landmark” series, but Daughtery brilliantly connects it to our great American story.