Wow! What a story! I would have been impressed if The Stout-Hearted Seven had been fiction. To know that it is non-fiction is exhilarating and tragic all at the same time. Reading true stories like this makes things like Marvel movies seem ridiculous. True courage and fortitude are not found in superheroes with capes but in stout-hearted people with a will to follow God’s leading and their own conviction.

I read the Sterling Point reprint of the original text written by Neta Lohnes Frazier. Frazier opens this memoir by explaining her personal relationship with two of the Sager sisters and pointing to her sources which were mostly primary source material. She explains that she has added dialogue but that even that is based on research and reasonable deduction. After she sets the stage, she begins at the beginning and tells the entire ordeal in the voice of an omniscient narrator. This book reads like an excellent Landmark Book or Messner Biography. It is easy to see why Sterling Books reprinted this one alongside the many Landmark reprints that they did. This is absolutely worth reading. And the audiobook is excellent.

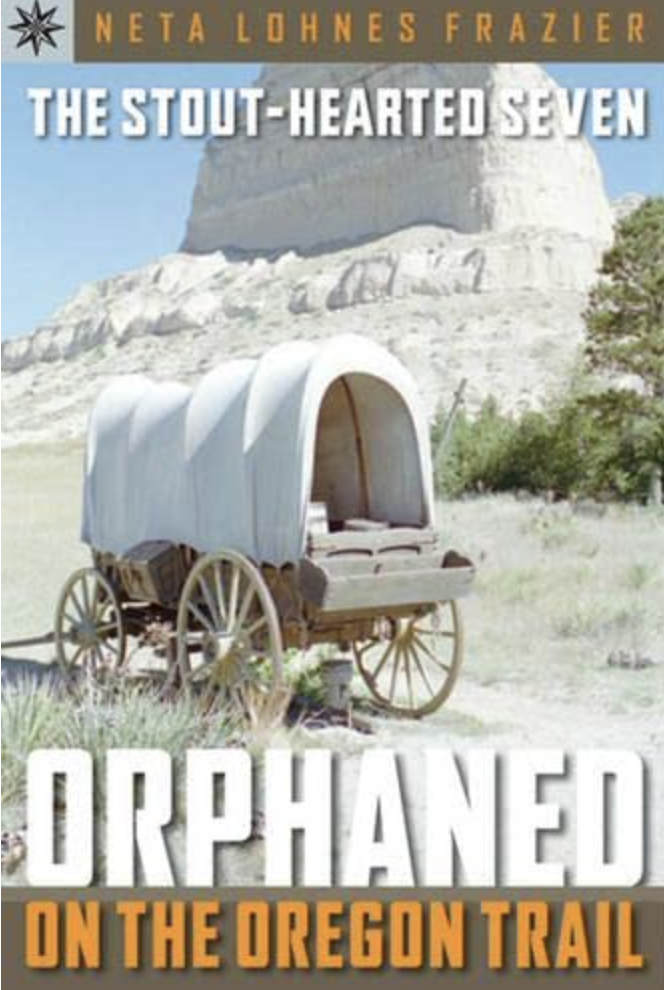

In 1844, Henry and Naomi Sager decided to join the wagon trains going from Missouri to Oregon. They packed up their six children and all of their belongings into a wagon with six oxen. Although not a trained doctor, Henry was wise with healing and made friends throughout the wagon train as he tended to the ailments and injuries of his fellow travelers.

Along the way, Naomi gave birth to the seventh Sager child. Their journey was, like most of the Oregon Trail treks, fraught with trouble. Along the way, Henry was plagued with camp fever and ultimately succumbed to his illness. Naomi and her children did all they could to rally because they had no other choice. Sadly, Naomi too gave into camp fever, and her baby was kindly passed from nursing mother to nursing mother throughout the wagon train, despite everyone’s extreme thirst and rampant hunger. The good men and women of the wagon train, most specifically William and Sally Shaw, took a special interest in the Sager children and made sure they did not go hungry nor had to ford rivers or overcome dangers alone.

When the immigrants reached present-day Walla Walla, Washington, missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman adopted the seven children and loved them for three years. As more immigrants came West, the native peoples of the West became more and more anxious about their hunting grounds. Sadly, however, the wagon trains also brought European diseases with them that the native people had no resistance to.

When, in 1847, a wagon train came through the Whitman missionary station with measles, it was devastating for the Cayuse people. Stirred up by bad actors and devastating grief over the destruction that the measles caused in their tribe, the Cayuse attacked Whitman station and killed the Whitmans and the two Sager boys along with many others.

For a month the survivors lived in terror of the Cayuse men who watched them and demanded work from them. During that month, several more women and children, including one of the Sager girls, died of measles while in captivity. Ultimately, Peter Skene Ogden from the Hudson’s Bay Company bought the freedom of the remaining women and children and moved them to Fort Vancouver.

This story is expertly well-written. It is exciting, and no one will escape tears when reading. Catherine Sager’s written account of their experience is the primary source material for this story and is widely considered to be one of the most authentic and compelling stories of the American westward expansion.

The reprint is well done, and the audio is a joy to listen to.