It is from numberless diverse acts of courage and belief that human history is shaped. Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current that can sweep down the mightiest wall.

Robert F. Kennedy, from the dedication page of Agent Most Wanted

Virginia Hall was an American woman, born in 1906 to a good family of “reduced means.” Her mother envisioned Virginia marrying well and restoring the family’s prestige and security. Virginia had other things in mind.

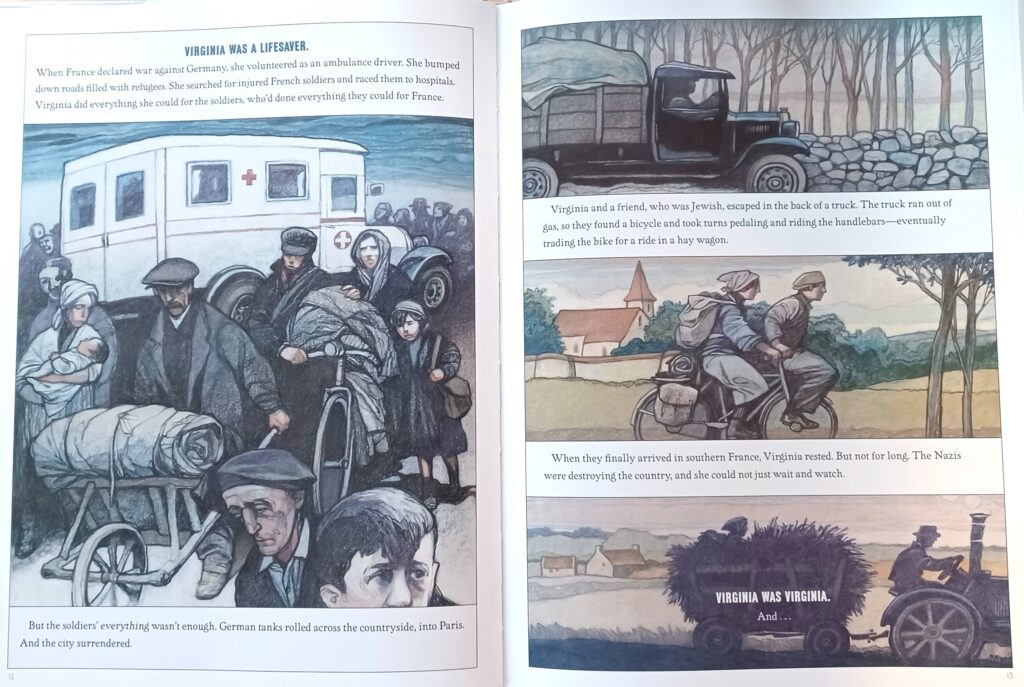

After college, that alone being unusual for a woman of her time, she spent seven years in the foreign service as a secretary. Not only did she long for more adventure, but she had also learned to love France and considered it her second home country. So, in 1940, she joined the French 9th Artillery Regiment as an ambulance driver.

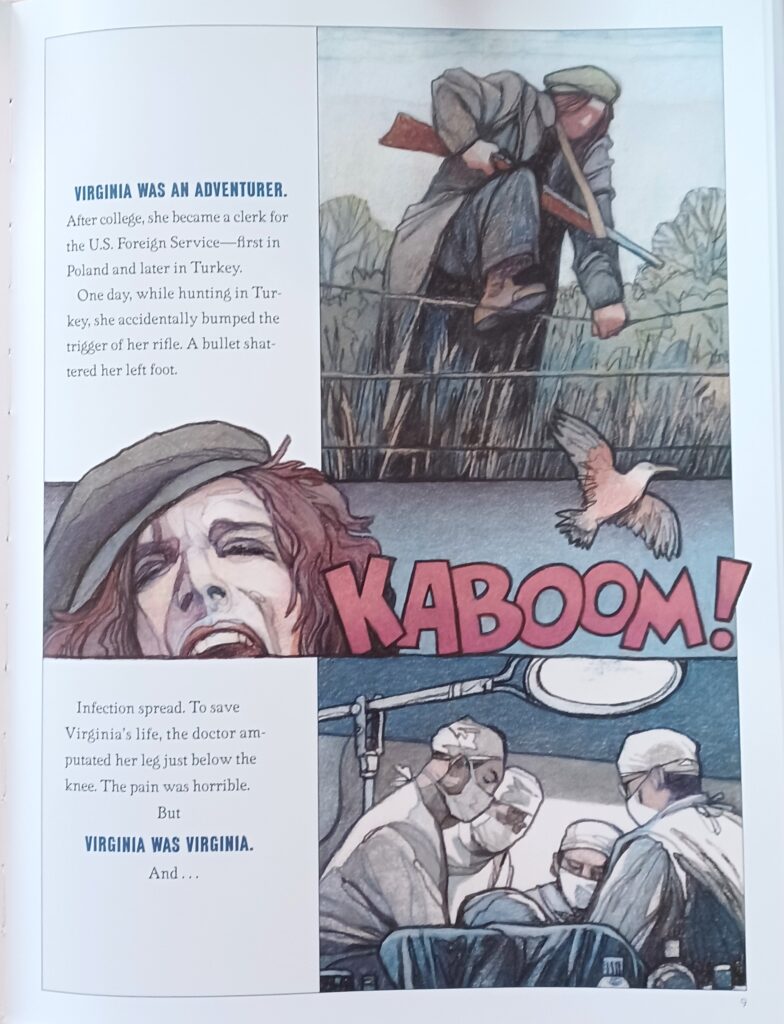

One thing she was careful to conceal from nearly everyone was the fact that, at the age of 27, as a result of a hunting accident, her left leg had been amputated below the knee. She walked with the aid of a wooden prosthetic which she named Cuthbert.

After France surrendered to Germany in 1940, Virginia went to London to find out if Britain could use her services against the enemy. She trained with the newly formed Special Operations Executive and was sent to Vichy, France in 1941. She became the first female field officer of the SOE.

From then until the end of WWII, whatever Virginia’s official orders and rank, she recruited for the French Resistance, established safe houses for escapees from Germany and downed allied pilots, and set up effective communications systems between France and Britain. She directed air drops of food, ammunition, and explosives, distributed money to Resistance cells, and organized hundreds of people working in dozens of different operations simultaneously. She even engineered a prison escape for twelve radio operators who had been held in a German prison for months. One historian called it “one of the war’s most useful operations of the kind.”

Whether they loved her or hated her, everyone who knew her considered her an amazing and memorable woman. Klaus Barbie, the infamous Butcher of Lyon became obsessed with finding the “Limping Lady of Lyon.” He had posters made and offered a huge reward for information leading to the arrest of “The Enemy’s Most Dangerous Spy.”

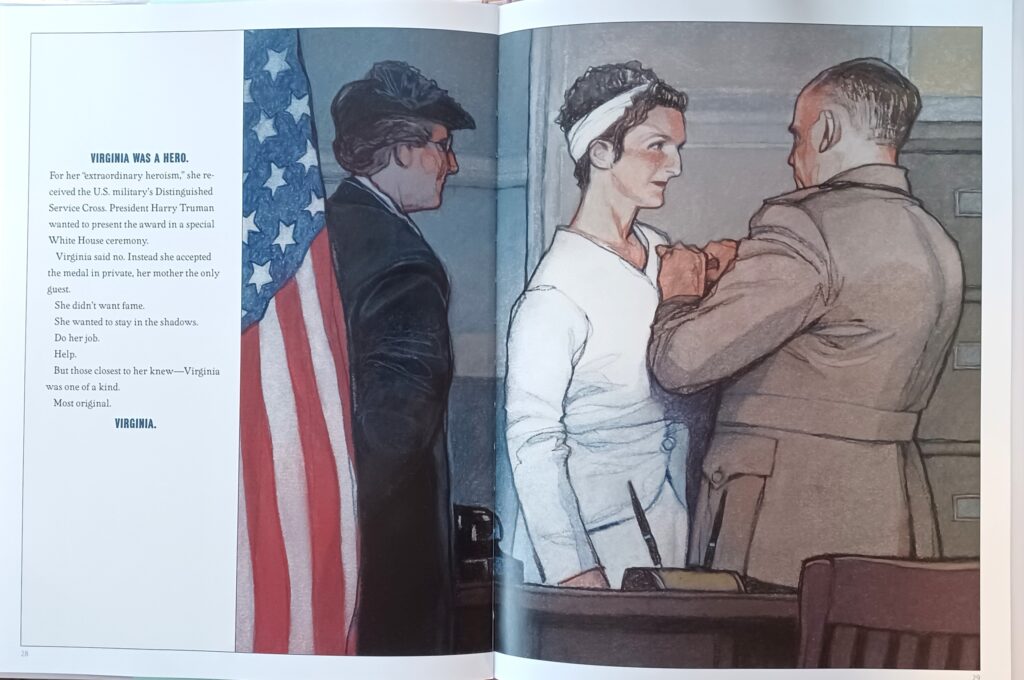

After the United States entered the war, Virginia joined the new intelligence agency, the OSS (Office of Strategic Services). The OSS was dismantled after the war, but the CIA was formed soon after, and Virginia was one of the first women to join that agency. As incredible as were her astounding feats in the field, during her entire career, Virginia was never given proper recognition for her skills and accomplishments because it was still considered ridiculous for a woman to be in command of men.

Virginia never told her own story because she didn’t feel she deserved any special recognition for doing what was right, and she had known too many people who had died because they talked too much. Nevertheless, she was the only civilian woman in WWII to be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism against the enemy.

I first read Virginia’s story in a book by Sonia Purnell, A Woman of No Importance. This is an excellently researched book and brims with details about Virginia’s Resistance work. The scope of the book is as breathtaking as the details of Virginia’s everyday life. This book is less than 300 pages long, but it was a slow read for me because of the intricate details complicated by changing code names and the various plots and operations. But it was well worth the effort.

Purnell doesn’t include unnecessarily grisly details, but she does include reports of torture, deaths, and brief descriptions of the work of prostitutes in the Resistance.

Agent Most Wanted is a young readers adaptation, by Sonia Purnell, of A Woman of No Importance. This book is about one hundred pages shorter than A Woman of No Importance. It is less detailed and moves more quickly, but it is still a well-told story of Virginia’s exploits. It would be suitable for most readers fourteen and older. It would be impossible to tell the story of Virginia’s work in Lyon without mentioning Germaine Guérin. Purnell describes the work of Germaine and her girls this way.

Germaine’s women took the biggest risks to provide Virginia with intelligence. They plied their clients with alcohol to loosen their tongues, and when the men were asleep, they rifled through their pockets for papers that might be of interest to the Resistance, and took photographs of them. They even risked putting itching powder into the men’s clothes to cause them discomfort and keep them from working. While once Virginia had nothing but contempt for prostitutes who entertained German clients, now she affectionately dubbed such women as her “tart friends.” Thanks to them, she knew “a hell of a lot!” about the German war effort, information that she swiftly passed straight back to London (page 43).

Another caution from page 117: “A few days later, she came across the severed heads of four friendly villagers.”

I also read The Spy with the Wooden Leg: The Story of Virginia Hall by Nancy Polette. This book is also written for young adults. It is 147 pages long with slightly larger type than Agent Most Wanted. Polette does an excellent job of telling a complicated story simply enough to be understood and enjoyed for younger readers. I didn’t note any cautions for the intended audience in this book.

And finally, Virginia Was a Spy: The Story of World War II Heroine Virginia Hall, a picture book introduction to this incredible woman by Catherine Urdahl.

Here is a link to this book on Biblioguides.